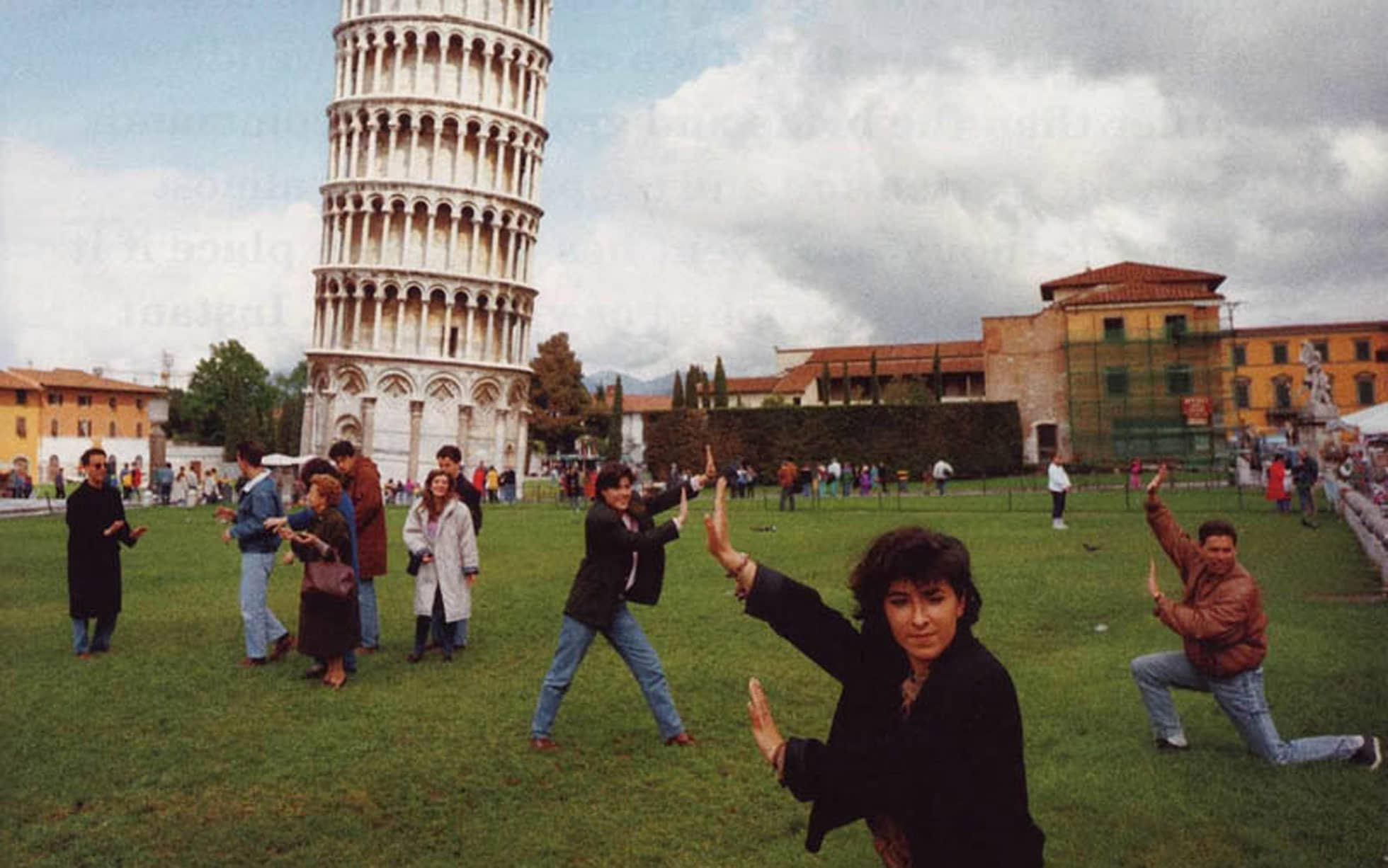

We are living in the era of information. It is easier than ever to visit the most remote sites of the world and have all the data we want from a place, even before getting there. Photography has an essential role in this phenomenon. First of all, it allows us to generate the imagery of what a place appears. The Internet is a visual world where all information enters through our sight. Accordingly, the most impactful images are the ones that take our attention the most, which brings us to the second: photography affects our experience once we are in place. We want to be the ones taking the best picture and show to the world that I was there too. There is so much information at the moment that people are more interested in finding new codes of expression than in the actual culture. As Susan Sontag points out in the text Notes on Camp, the style can be more important than the content itself. All in all, the photographic experience has changed.

The images that we see in a book or Google Images, for example, seem to be more objective than the ones we find on social media platforms but still, they all generate a pre-conceived image of a place that has been somehow curated.

However, there are always two sides to the coin. In the project Greetings from Barcelona a group of photographers question the ideal postcard images that are sold to the tourists and try to give a more accurate view of the city through their photographic view.

Media has relevant repercussions on photogenic locations. For example, when Game of Thrones was shot in San Juan de Geztelugatxe in the Basque Country, Spain, tourism in the area increased so much that implications were devastating for the ecological and the social environment of the region.

This phenom has affected mostly locations, but the same effect has affected works of art. The Louvre is the most visited museum in the world, with more than 9,5 million visits in 2019. Its principal attraction is the Mona Lisa. However, visitors usually remark The painting is too small, and the room is too crowded. I can see it better in a book or on the Internet. This affirmation might seem accurate if we think that the time that a person looks at the artwork is of seconds, and usually it happens through a screen or a lens.

In this case, as Walter Benjamin comments in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the aura of the artwork is lost. I would add that similarly, the aura of a place is lost too. The possibility of enjoying a landscape as a naive and sincere spot disappears when trying to capture it in a photograph.